A conversation with Jonathan Frederick Walz, Ph.D., Director of Curatorial Affairs & Curator of American Art, at the Columbus Museum. He is curator of the exhibition Alma W. Thomas: Everything Is Beautiful, which stats a national tour on July 9 at the Chrysler Museum of Art in Norfolk, Virginia. The exhibition concludes in Thomas’ hometown at the Columbus Museum, where it will be on view July 1 – Sept. 25, 2022.

You’ve said that there are a lot of misconceptions and misinformation regarding Alma Thomas and her art. How will this exhibition help correct some of those?

“We hope the exhibition will really help dispel the myth that she stopped teaching in 1960 and only at that point began to make art.

What’s great about the Columbus Museum’s holdings is that we can really talk about a much longer arc of her development. Most exhibitions start with her work in the 1950s, but we have pieces from the1920s and 1930s at the Museum, and from the ‘50s, 60s, and 70s as well. We’re really trying to demonstrate that she was creative throughout her life. Another myth is that people assume that she stopped teaching when she left the classroom. In fact, she’s one of these people who just has teaching and education and love of youth in their bones. She may have stopped formal classroom teaching in 1960, but she found other avenues to share her gifts for teaching art to younger people.

She was a member of St. Luke’s Episcopal Church, which was just a few doors down from her home on 15th Street in Washington. She used the church as a hub for offering programs to youth. To keep them off the streets and teach them skills and character-building.”

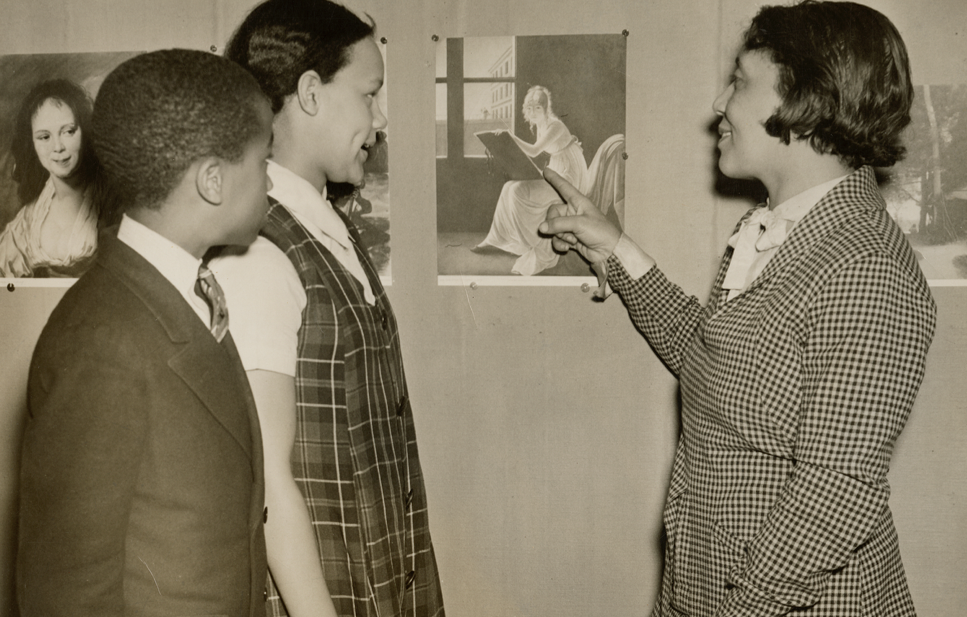

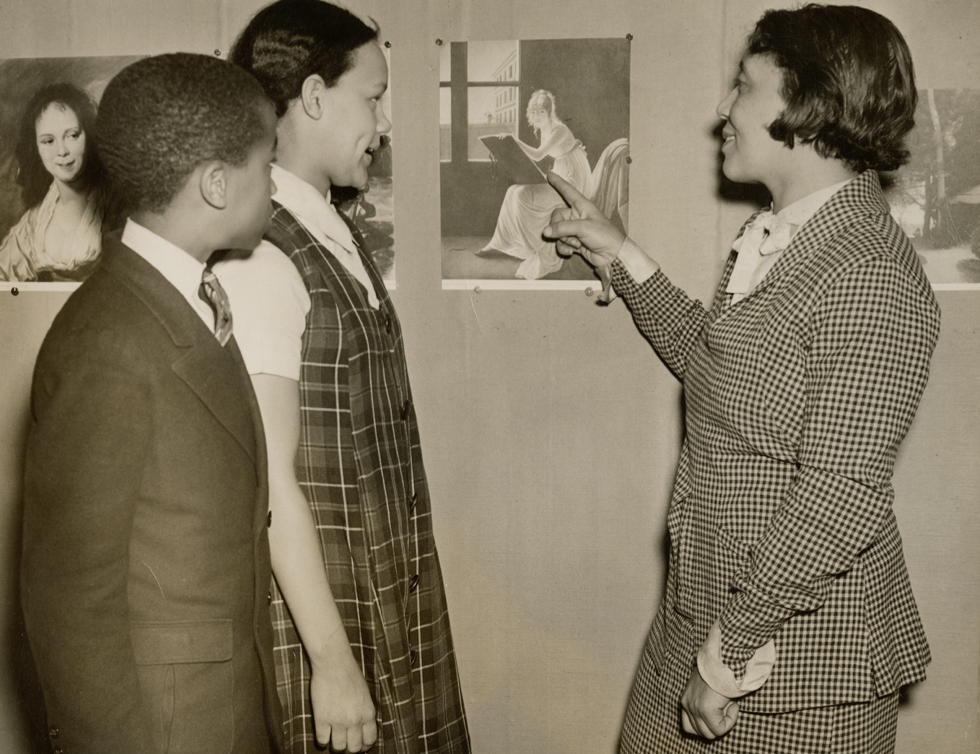

Alma Thomas Papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution

What inspired the title of this exhibition, Everything Is Beautiful? |

“We have at least two, reliable sources stating that her favorite song was Ray Stevens’ chart-topping pop hit “Everything Is Beautiful (In Its Own Way).” We wanted to draw attention to Thomas’s love of music, but beauty is a huge theme of the show. Her devotion to this pursuit of beauty took form in so many aspects of her life. But beauty in the way she understood it— it was something that she got every morning and went and looked for and tried to create for herself and her community.”

When Alma moved with her family to Washington, D.C. as a teen, she reportedly went to her new school, saw her art classroom, and said it felt like “entering heaven.” What do you think she meant by that? And what does it tell us about Columbus at the time?

“One of the primary reasons the Thomas family leaves the area—which is a sad part of our city’s history, but it is what happened—is that Black education at the time only went through ninth grade, while the white schools went through twelfth.

Her mother had a very strong family tradition about education. How important it was. How it works as a way to better yourself, and to better yourself so that you can bring the community along with you. Thomas’s parents realized, ‘Education is how to open doors and get ahead in life, so we have to do better than just a ninth-grade education.’

Having grown up here, she played with the local clay as a kid. From that, she had a real sense that she really liked to make things, that it was really satisfying to her. So of course, this room at Armstrong Manual Training School in Washington is going to be heaven, because it’s full of all the materials and tools that she could ever want, there for her to use.

Imagine her seeing all of these desks and knowing that she wasn’t going to be alone but with other students as interested as she was in making things! So to her, it was paradise. I truly believe she walked into that classroom and felt, ‘I belong here.’

white Rose Hill neighborhood. Photo by Frankk Etheridge

Even though she acknowledged challenges she faced as a black female artist, Thomas did not incorporate racial or feminist issues in her art, believing rather that the creative spirit transcends race and gender. As we undergo a cultural reckoning that’s transforming America’s understanding of itself, what do you think she would feel about American today?

“This is a simple question that deserves a complex response. She comes of age as an artist in DC, when she’s operating under the late 19th-, early 20th-century belief that African Americans are equal to other Americans, and it’s about assimilating — basically the “melting pot” idea.

She considered herself an American, period. No qualifier. She never denied that she was Black. But being an artist and being an American is how she described herself. Even though I think she would have said in the ‘70s that she was interested in Civil Rights, at the same time, I think she was kind of like, ‘Everybody’s making too much of a big deal about this. Can’t we all just get along? We’re all Americans. We can figure this out, right?’ I think she was genuinely puzzled by the Black Power movement. But, at the same time, she had also had an experience with the Klan when she was a child here. So she knew the other side of the story, too. That the struggle for equality was ongoing. She really embodies that early 20th-century belief that, through hard work and excelling at things like the arts and sciences, Blacks will overcome negative stereotypes and demonstrate that they’re equal to whites.

When civil rights issues come to a head in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s and the Black Power Movement takes the stage, and the Black Arts Movement arises alongside it, Thomas didn’t deviate from what she was doing at the time— nature-based abstraction, seemingly without any (socio-)political content. The Black Arts Movement, in support of the Black Power Movement, dictated that, ‘If you’re painting abstraction, that’s from Europe. And we don’t like Europe, we don’t want to acknowledge Europe as the progenitor of culture, of civilization. We want to acknowledge the primacy of Africa for Black people, that Africa also produced culture and civilization. So you see a lot of incorporation of African imagery in painting at the time and African Americans dressing in African clothing, which she considered a kind of playacting.

She understood that the Black experience is not monolithic and that the African American experience is different from the African experience. She believed strongly that African American creatives should make work based on their experiences in the United States, rather than about the glittering generalities of a place they hadn’t experienced firsthand. And she felt like, if we can overlook all of the ugliness and get to this place of transcendental beauty, that’s what’s going to bring everybody together.”

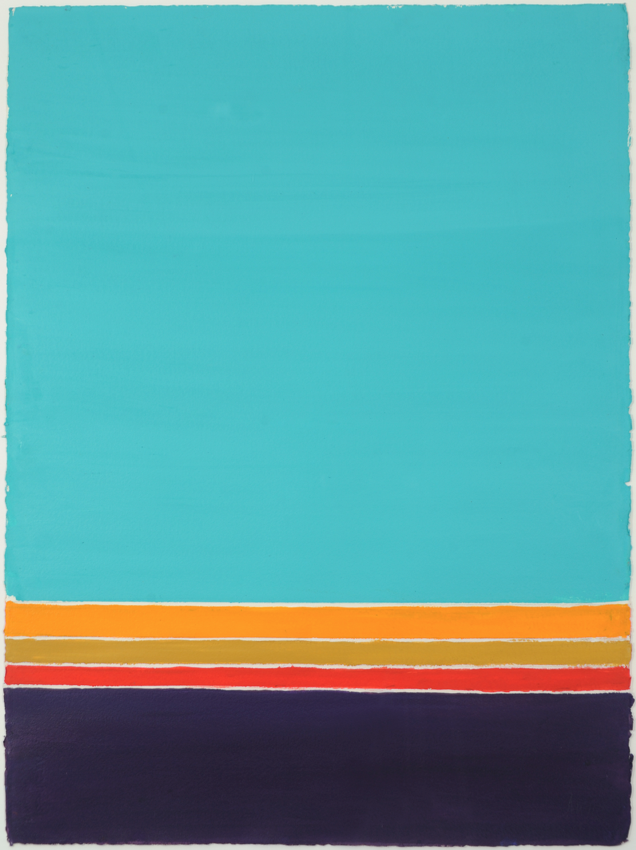

1966, acrylic on canvas

Collection of The Columbus Museum

1970, acrylic on canvas

1974, acrylic on paper

Why do you think all face masks featuring Thomas’ paintings have been so popular during the pandemic?

“She becomes a symbolic figure once you start to learn about her and find out she was a school teacher for 35 years, led this exemplary life, and she’s also very determined and seems to overcome these obstacles in our way.

But, at the end of the day, if you don’t know any of that and you just go to a museum and you see one of her paintings on the wall there. You’re attracted to them because they are colorful and they are nature-based. Nature is a fairly Universal experience for people and so it’s relatable.

And it’s approachable, too. Like you think, ‘I could make a painting like this if I put my mind to it,’ but at the same time knowing, by looking at it, that it’s really sophisticated.

Her work isn’t doesn’t seem to be political, right? So you’re thinking about what you’re going to put on as your face mask and what you should go for this month. They just released this sardonic Barbara Kruger that is criticizing people with money. Should I go with this? Or with the one with really colorful details that looks good with my sweater?’

I just think Alma Thomas’ work is super approachable and it lends itself to wanting to share. If you look at the Alma Thomas hashtag on Instagram, somebody is posting something about her or one of her paintings everyday. I’m not even lying — I check. She just has an appeal.”

Black and white photograph Alma W. Thomas Papers, The Columbus Museum