Author, Illustrator, Mystic

Why do you think your book A Little Bit of Angels: An Introduction to Spirit Guidance has done so well as far as sales? Why does this book resonate with so many people?

“I hope a book like that does resonate with people because spiritual themes really permeate our actual, practical lives.

One of the reasons I love doing what I do is trying to get our culture to be more open to the creative, intuitive, spiritual aspect of our humanness. I think we’re so rational and logical and so embedded in that we have suffered a lot. If people are interested in those things — and I think people are traditionally very interested in angels.

Used to be, when I first started doing this work from doing children’s books — if you even said the word intuition, it was almost déclassé.

Whereas now you hear about it on commercials. Now, everyone knows you have to be more intuitive, not just rational and practical. But I had to take a risk on earlier being on the people going ahead and saying this is good stuff. This is important for us.

I think people are interested in the angel book because people do sometimes feel they’ve been helped by an angel. They have unseen helpers in some way. Or they’ve had experiences they can’t explain. And maybe we really want angels to be real so much so that, in a way, that helps make them real.”

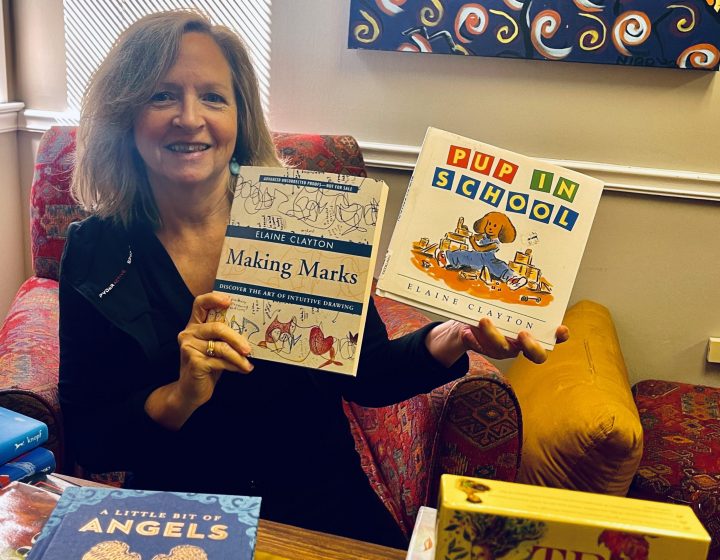

Another book of yours, Marking Marks, explores the idea of intuitive drawing. How would you describe that process?

“I think we’re born mark makers. It is something innate. The idea that we’re present, we’re alive, and we make a difference.

The first thing a baby does when they’re able to sit up, they move the food around on the tray, because they notice not only does it have a texture, but also visually it does something. When kids are really tiny and they have something to make a mark with, they of course go to a blank wall. It’s just waiting for something to happen.

We’re so privileged to have an education and there’s so much for us to cover in teaching literacy, mathematics, and all that, but what has been sacrificed is that beautiful creative, natural impulse to just make marks. In other words, to draw freely and expressively. We’ve put that aside. It’s almost like recess: ‘We have 20 minutes for things like that.’ Or, ‘Do that after school.’

And if the kid who does draw real freely, begins to get into the age of reason, your developmental stage advances, and you want the freedom to want to do a drawing that looks like an object that does resemble — a person, place, or thing.

Then comes a lot of self-criticism and commentary from others. ‘It doesn’t look like a tree. Nice try.’ ‘That looks like a scribble.’ We have so many ways of judging mark making but it’s this wonderful way for humans to get in touch with their creative power.

I feel like we should never have lost it. Individuals should not lose that ever. But most adults I talk to doing workshops, they’ll say, ‘I love to draw but I’m not very good at it. I love to draw but I don’t have time.’ But if you ask the same person, ‘What do you love the most about the world?’ ‘Oh, I don’t know.’

You have to have quiet, creative time to ask yourself questions that are important.”

You’ve led these workshops on intuitive drawing — saying it enhances creativity, empathy, and even self-confidence. How do you develop these qualities out of intuitive drawing?

“If you value your creative impulse and expression, then that takes you to a place where you reflect. You don’t just make a mark — you look at it, too.

The reflection part of gazing at what’s been drawn is where huge things happen. It’s like meditation or prayer. If you take time to breathe and be silent, while at the same time you’re being creative, you’re open to thinking about the marks you have made and what they mean to you.

It’s finding meaning. A human being in search of meaning is really open-hearted and open-minded. Then you have a lot more potential to not just respect another person’s creative impulse and expression and what they have discovered as meaningful to them, you have a natural honoring for it and love for it.

I think empathy is missing because we don’t encourage people to know what you love, know what you feel good about yourself, how to honor the feelings of others through that self-honoring. It goes hand-in-hand.”

in 1993 and remains the work she is most proud of.

What led you on the career path to becoming a book illustrator?

“I left Columbus High and did some volunteer work that was real meaningful to me. Really hard, tough, at the age of 17, spending a summer doing community organizing in the rural South, where people don’t have running water. I was at a Caesar Chavez migrant camp in Mobile.

I was learning a lot about human suffering and systems that need improvement. I had that weighing on me. I went to Spring Hill [College] at first and realized during my short time there I loved drawing. It was so amazing to me I decided I was cut out for art school.

I went to Atlanta College of Art, which is now Savannah College of Art and Design. You were in the studio all day with working artists. I learned so much and I loved it so much. I had been working at the High Museum in the junior gallery and teaching summer camp. It was going to be children’s books or graphic novels. Graphic novels, in 1981, was such an underground movement that it was something I didn’t know I could quite figure out how to do. It made sense to do children’s books.

Working with 6 and 7 year olds teaching creative writing, I’d start by saying, ‘I’m going to draw a picture for you,’ I would start drawing on the whiteboard, just making up stories. One day, a girl stood up and said, ‘You’re not erasing that.’ I thought, ‘Okay, I’ll just put it on paper.’

Then I got the idea that it would be good to show them to a publisher. What I didn’t know was how long it took a book to get published. These students were in junior high by the time the book came out.”

What forces shaped your career path?

“I think because the motivation to make something that would make someone feel better was very inspired by anything that would make someone feel more whole. Children’s books are really into that. These picture books are a wonderful art form.

On a practical side, I wouldn’t feel happy unless I was writing or doing editorial artwork. I also did a lot of spiritual work on the side. Those are the internal motivations.

But then come the practical things: Do it for a living? How do you make that happen? It almost seemed like, in my 20s, I would rather die than not make it happen. People would pat me on the head and say, ‘Oh, that’s a nice dream you have.’ I thought, ‘It’s not really a dream. I really want it to be true.’

So I went from saying, ‘I want to do children’s books,’ to, ‘I’m doing children’s books.’ It took a lot of prayers, a lot of preparation. Forces that I couldn’t have put together.

I like to see forces coming together. You don’t have control over a lot of stuff. You can do your best and do what you can do. But in terms of my sense of faith, some of the best things that happen to us, I could not make happen.”

Where does the line between the physical and spiritual realms exist?

“In a Christian worldview, your body is the sinner, your soul is what you’re wanting to honor more, and so you’re slapping yourself all the time.

In a Judaic point of view, it’s not quite the same, because the body is not perceived as being in conflict with the aoul.

If you take both of those traditions and play with that, it’s really fun. That’s one way to answer.

The other way is that every cell of our being is permeated with what I would call the Light of the Soul. We’re not separate from it. The idea that our bodies are instruments of the divine. It’s a gift to have a body and be alive for a time.”

What inspires you?

“People inspire me.

I’ll be in a bad mood, walking into the grocery store, chewing gum, in my head with whatever bad-mood thought I have in my head. If I look up at someone and they’re beautiful and they don’t realize there’s a tree arching over them, there’s a whole stage set up for them to be just this beautiful presence.

That inspires me. The ordinary — how unordinary it is.

What else inspires me is trying to understand what God means to be. Honestly, that’s what I live for.”

Age: 60

Education: Columbus High School, Class of 1979. Atlanta College of Art. Master’s degree from School of Visual Arts in Manhattan.

Favorite mystic: “Edgar Cayce. He was called ‘The Sleeping Prophet.’ He was southern. He would go into a trance, a sort of sleep state. People would ask him medical questions, and he would answer in ways, he was a Baptist Sunday School teacher, while he was in this trance state. A lot of the things we use medically now are things he thought of back in the 30s and 40s. Magnetic resonance. Ultrasound. He’s a wonderful visionary to read about. He talked about something I was inspired to paint about a long time ago — Earth changes. Edgar Cayce said the poles were going to shift. You can go onto the NASA site and see what this change looks like. It’s not balanced right, leading to extreme weather, violence of all types. We’re living in those times now.”

Favorite book illustrator: Garth Williams (Charlotte’s Web, Stuart Little)

3 qualities of a Reiki Master:

1) “Willingness and deep aspiration to help others to be healed.

2) Discipline. You have to be attuned to it and you have to go through the steps to do that.

3) Keeping your ego out of it.”

3 guests, living or dead, you would invite for a dinner party:

1) “An ancestor called the Ari. He was a rabbi who came up with the idea of the Tree of Life. So fantastic and mystical. I ask in dreams to have conversations with him.

2) Abraham Lincoln. He would be so interesting.

3) Can this chair remain open? There’s so many.”

Published work you’re most proud of: “The first book that was by Crown, Pup in School. Just breaking in and finally having that first picture book was such a big deal to me. The theme of it was bullying before there were bullying books. But I wouldn’t put bullying in the title because I thought applying that label could also be a bullying thing.”