by Natalia N. Temesgen

One summer nearly a century ago, Columbus, Georgia hosted two literary giants for a brief time as they road-tripped through the state.

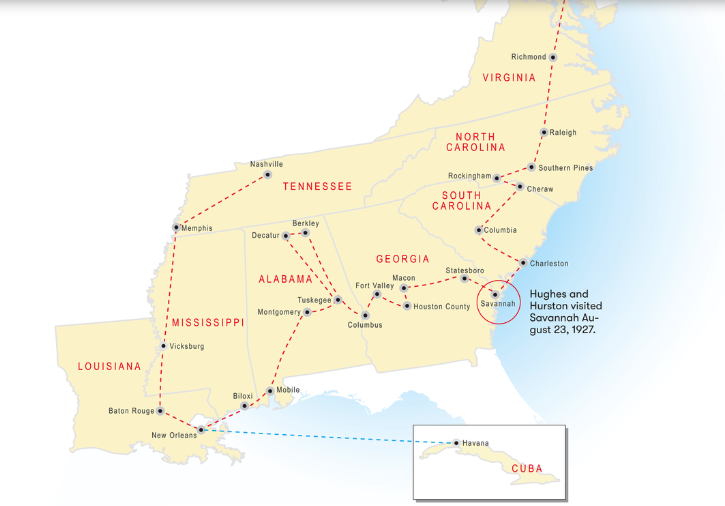

Langston Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston, arguably the most significant writers of the Harlem Renaissance, came into Columbus on August 15, 1927 after a week in Tuskegee, Alabama, chugging along in Hurston’s old Nash coupe.

Hughes, prolific writer of such notable poems as “I Too” and “Mother to Son,” was in Mobile, Alabama during a stretch of research and speaking engagements when he ran into Hurston, who was doing research for a new book. On a whim, they decided to travel together and spent the following weeks driving across the Southeast, visiting black professionals, educators, and artists, and interviewing the humbler black residents of each community.

It became evident to Hughes, who was from the Midwest and lived in Harlem, that many black people in the segregated South were deeply caught up in the criminal justice system. Mob lynchings and shootings of black people were frequent enough to leave them in a state of terror; poverty and under-education were common among black families; and when the formal criminal-justice system intervened—sometimes bringing criminal charges, but sometimes bringing no official charges at all—the outcome was hard prison labor. The chain gangs of the 1920s were not just the stuff of old blues songs. Even here in Muscogee County, they were very real.

As they traveled into Georgia, Hughes observed in his notebook, “Saw man driving goat cart in Columbus. Passed many gourds for bee-martins high on poles.” Shortly thereafter, they were into Talbotton and then Fort Valley. It appears they didn’t stay long in our city.

Approaching Savannah one evening, they encountered a young black man named Ed Pinkney, a fugitive from a chain gang. He looked afraid to be caught, but asked them for a ride to Atlanta, where his new wife was waiting for him. After getting into a fight back home, he was picked up by officers then shipped to a Savannah chain gang where he was subject to physical violence by guards and hard day labor. When the authors invited him to travel with them up North, where he would more likely experience a less violent and oppressed existence, Pinkney declined. He was preoccupied with meeting his wife in Atlanta; when Hughes and Hurston looked for him the next morning they couldn’t find him again.

Hughes recounted that story as the forward to a novel called “Georgia Nigger,” written by John Spivak, a white investigative journalist. His novel was intended as an expose of the brutal forced labor system of the chain gangs in the Deep South. In the novel, a stockade—similar in many ways to the Columbus Stockade—houses many black and some white prisoners in inhumane conditions, until they rise and are set out to work the fields and on construction projects, connected by iron leg shackles and chains. In this excerpt, you can clearly picture the cruelties Spivak witnessed and heard in interviews while traveling to chain gangs all over Georgia (including in Muscogee County):

“The huge negro moved restlessly. His legs

hurt. A steel spike resembling an ordinary

pick extended ten inches in front and behind

each ankle. The twenty-pound weight had rubbed

against his feet until one leg had become infected.

Shackle poison convicts called it.

He had asked for a doctor and the guard’s

fist had crashed against his mouth. That had

been yesterday and he had not complained

again though the throbbing pain made it hard

to work and impossible to sleep.”

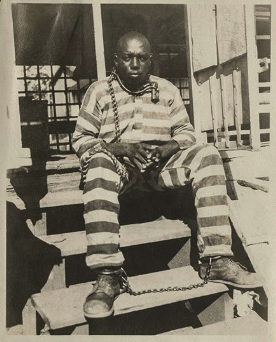

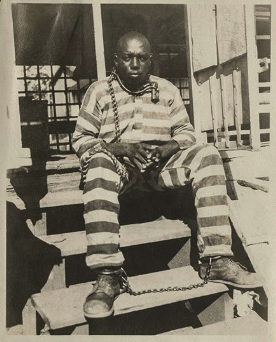

Spivak took a photograph of a black inmate in the Muscogee County Jail in 1931. He wears a heavy-looking neck iron, which was reportedly around his neck for two months.

Image courtesy Harry Ranson Center, University of Texas-Austin

Today, Columbus, Georgia has the largest prison work camp in the state. While some of the inmates working on sanitation, landfill, and recycling are paid a small daily wage to be received upon release from prison, many others working in maintenance, street cleanup and transportation receive no wages. The argument as to whether this labor is too closely reminiscent of slavery or chain-gang labor has been ongoing for many years by leaders within our community. There is also the reality that without this prison work camp, Columbus residents would be paying far more to have their garbage and recycling taken, their streets beautified, and their golf courses manicured.

While the writings of Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, and John Spivak illuminated the pains, hopes, and struggles of Southern black Americans in the early part of the 20th century, the writers themselves were able to live in relative peace once their assignments were completed.

Similarly, we can discuss the topic here in this forum, but just as easily turn off the screen, put the trash on the curb, and never consider any of this again. Even the old “Columbus Stockade Blues” have enjoyed decades of fame in the country/blues scene. But the subject matter covered in the lyrics still haunt. They remind me of the countless lives that were lost and forgotten on the chain gang and in the prisons of Columbus, only occasionally lifted to public view by an artist or a writer for all to glimpse.

“Way down in Columbus, Georgia,

Wanna be back in Tennessee,

Way down in that ol’ Columbus Stockade,

My friends have turned their backs on me.

Go and leave me if you wish to,

Never let me cross your mind.”—Stockade Blues, Darby and Tarlton, 1927

Natalia N. Temesgen

Assistant Professor of Creative Writing

Columbus State University

“Caught Up” is a series of profiles of diverse perspectives and experience with the criminal-justice system in the Chattahoochee Valley. It is funded by an Action Grant from the Community Foundation of the Chattahoochee Valley.

Thanks for addressing this aspect of the prison-industrial-complex, which is thriving today in our community and in communities all around the US. Many of our laws are not made to create a moral and balanced society but to create a steady stream of cheap, prison labor, and it’s this labor that cities like ours utilize for essential public services.

These “inmates” are often looked upon with fear and/or irrational judgment, treated as if they’re second class…and these are the human beings that haul off our trash, maintain our public parks, and more. Do you actually think that if we collectively do not care for them, that they will properly care for us? Some do, but I totally understand why most would not.

It’s a completely unsustainable system that we’re addicted to, and it is causing so much more harm than good.

And since for-profit corporations stand to lose massive contracts and their cheap labor if we organize to constructively discuss this project, an incredible amount of lobbying stands in the way of our democratic discourse.

But we MUST wake up to not only this issue, but the myriad of issues that affect us all, which keep us distracted, divided, stressed, and struggling. If we can properly acknowledge and address the prison-industrial-complex, we can bring great healing to our community and to our nation.