“Caught Up: Criminal Justice in the Chattahoochee Valley” Vol. 1

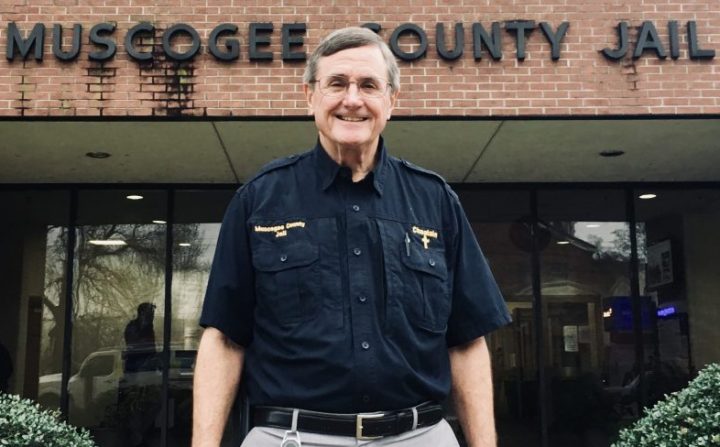

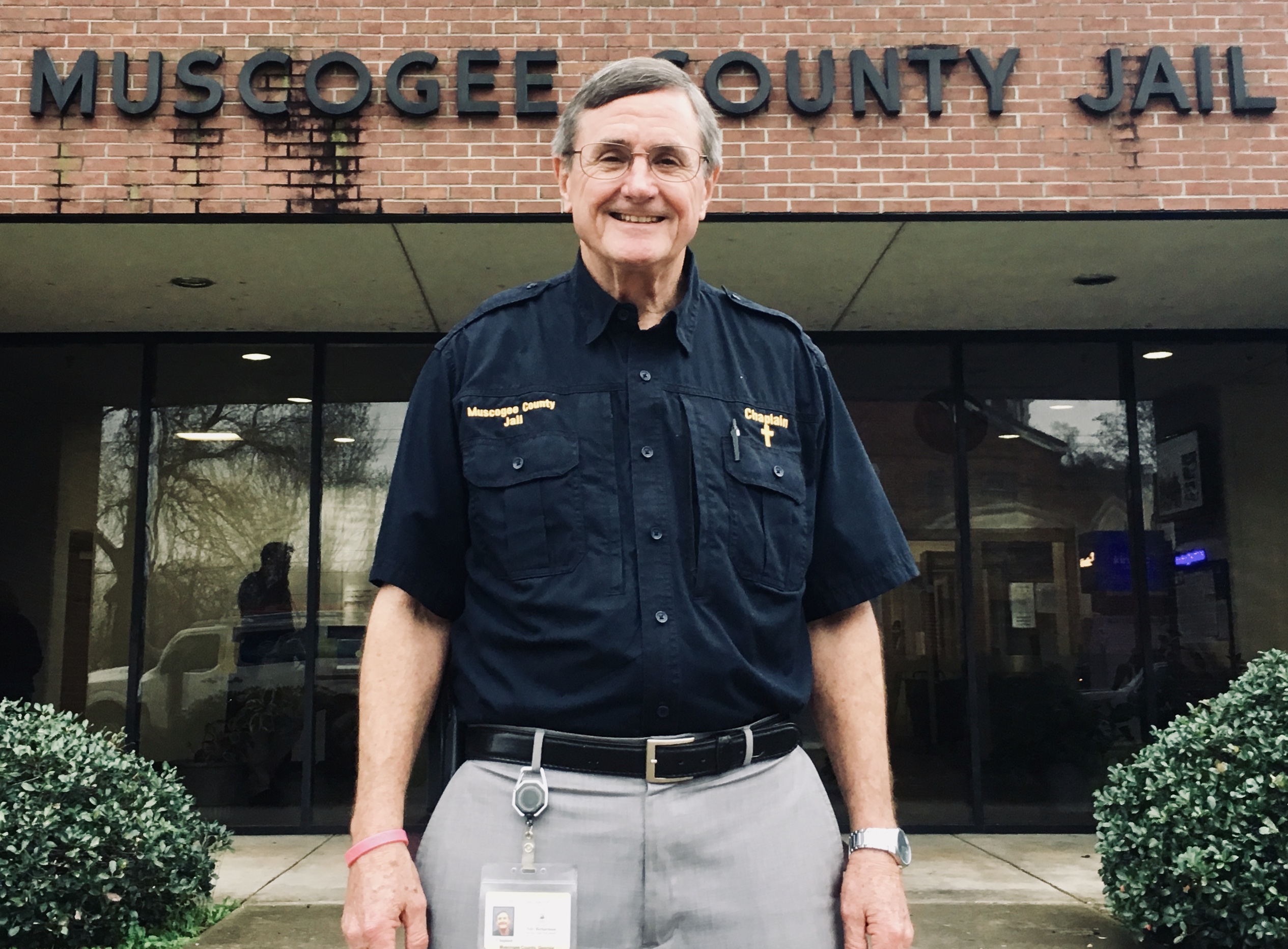

Like all other sheriff deputies reporting for duty at Muscogee County Jail, Chaplain Neil Richardson doesn’t carry a gun at work.

“It’d just end up getting used against you,” Richardson says during a recent tour of the city facility.

He explains matter-of-factly the policy against the 100 or so Muscogee County Sheriff’s Dept. correctional officers carrying a gun while on duty. Rather, the guards—who must undergo annual use-of-force training (self-defense, de-escalation techniques)—are equipped with tasers.

“All tasers have cameras on them,” explains Richardson. “And they have red lights to give one-last warning: ‘Are you sure you really want to do this next move?’”

Hired 9 years ago to administer to inmates’ spiritual needs, Richardson works five 12-hour shifts one week, two 12-hour shifts the next week, in 1 of 4 squads forming MCJ’s security apparatus.

“I think that it’s a higher calling,” Richardson says of the call to serve as a deputy on detail at the jail. “The officers are normal folks. They have a sick mother to take care of at home, too. I work with regular people who care for this community.”

Officers are required to place firearms in a locker upon clocking into work in an area dubbed the ‘Sally Port’ at the jail’s rear, secured entrance along 9th Street.

“You go into this job knowing that you’re going to put your hands on somebody; at some point, you’re going to have to defend yourself,” Richardson says.

“If you have protecting the community as your mission, you go into it with the mindset, ‘I’m doing my part to protect Columbus, Georgia.’”

The Sally Port is where officers first enter the workplace.

It’s also where inmates enter the jail.

“The first thing that happens when a guy gets in here is that his tattoos get looked at,” the chaplain explains of the intake process. “There are gangs and the way to predict that is with tattoos. Some prison gangs have some real identifiable tattoos. If a local street gang has begun doing tats, we’ll know. We have a gang intelligence partner—he’s the one who testifies in state court on gang charges. He’ll take a look if we need to ID a tat.”

Two factors determine where a new arrival lands inside MCJ, Richardson says: gang affiliation plus past behavior while incarcerated.

“We have two obligations here,” he says. “To keep the community safe by taking a potential risk off the streets. And to protect the inmate. They have been arrested but not tried yet, and we have to look out for their best interest.”

“Now, is that a guarantee there’s no violence in the facility?” Richards asks. “No. Our job as a security apparatus is to make sure it’s rare and hard to pull off.”

Has he ever witnessed violence while at work?

“Yes.”

“I can’t remember the last inmate death,” he replies before recalling 3 over his 9 years as MCJ chaplain.

However, 4 inmate deaths in the first 8 months of 2017 prompted an investigation by the Georgia Bureau of Investigation. The GBI probe determined in January 2018 that 3 deaths were due to natural causes and 1 by suicide.

Among the 3 deaths determined to be from natural causes, Feaginess Wood was found unresponsive in a pool of his own blood with a laceration above his left eye.

The 31 year old was arrested June 13, 2017 on child-molestation charges after blowing kisses and exposing himself to a 3-year-old girl near a home off Wynnton Road. Wood died July 1 at then-Midtown Medical Center’s emergency room. Jail video shows him enter a cell with another inmate prior to his death inside MCJ’s mental-health dorm.

Richardson says Wood’s family told him that they have a history of brain aneurysms, thus it was likely he suffered one then fell and hit his head during such an episode.

In 2013, MCJ saw one murder and the suicide of Lori Carroll, a mentally-ill 46 year old locked up for disorderly conduct who witnesses say beat herself to death during a psychotic episode as they watched.

In the first two months of 2019, inmates’ eyes were stabbed with forks—resulting in blindness and stabbed-out eyeballs—in 4 separate attacks MCSD officials suspect to be gang-related.

Muscogee County Jail 2019

“The number-one group for incarceration increase in America right now is veterans”

“Talk to me on the box,” Richardson says to several fellow officers, approaching him to ask for counsel on a variety of concerns as they make the rounds.

Inmates tap the inside glass of their cellblock to wave hello and make gestures in request of a visit or call from the chaplain. He walks on the air of a well-met fella, wrapped in an aura of Christ-like humility and equal respect for all he encounters, while expertly navigating the labyrinth of interior jail hallways.

Waiting at an elevator, Richardson is stopped by a man with Georgia Dept. of Community Supervision—the agency inside the Dept. of Community Services that since 2015 has managed the state’s consolidated probation/parole programs.

He tells of a probationer who started smoking crack cocaine again, was homeless, and in need of treatment. Richardson says Grace House—transitional housing for men that is one of several halfway-houses within SafeHouse Ministries, which he leads in concert with the nonprofit’s board of trustees—is four heads over their bed-count at the moment. However, he gives the DCS officer a card and name to call.

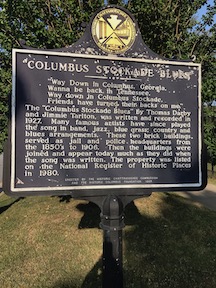

Two elevator rides land inside the “new tower.” It opened in December 2002 at a cost of roughly $17 million to offer 3 floors with 8 dorm cells each. It also contains expanded administrative areas, a larger medical facility, and additional clinic beds. The 1850s structure at 622 10th St. made famous in “Columbus Stockade Blues” was molded in 1939 to a facility that most recently housed weekend detainees (DUI, petty theft, etc.) until the U.S. Dept. of Justice ordered it closed. It now serves as storage space.

In 2009, Columbus voters approved a SPLOST for one penny dedicated to public-safety projects, including a new MCJ for an estimated $44 million. After the transition from Sheriff John Darr to current Sheriff Donna Tompkins, it was revealed that the money was spent during the last years of Darr’s administration.

On the new tower’s first floor, a variety of jail operations extend out from “central command:” a high-tech monitoring of all jail functions at once, it seems, manned by 3 big men in the familiar MCSD black polo shirts and khaki pants. Cells marked HID are reserved for serious medical conditions. There’s an A/V cell for meetings with attorneys where officers are not allowed to listen in. Conjugal visits are “the stuff of fiction and by-gone times,” Richardson replies when asked about such lodgings.

The dental clinic shares space with the mental-health clinic, the hub of operations managed by local agency New Horizons.

“Until six years ago, a mental-health crisis put you in lockdown,” Richardson says, noting it now consists of 23 hours solitary confinement, 1 hour recreation. “This is one of the first jail facilities to make that transition.”

Inmates seen mopping floors, folding laundry, etc., wear yellow, red, or blue shirts. That’s for the trustee program, Richardson explains, with trustees compensated in labor/reduced time rations of either 4 to 1 or 2 to 1, depending on their sentence. MCJ provides inmate labor to the Government Center and to Parks and Recreation. Garbage detail is manned by men “up the road” at Muscogee County Prison, where you’re sent if convicted but sentenced to less than a year incarcerated.

The jail population breaks down to about 1,000 men and 140 women at any given time, the chaplain estimates. Everyone is given 1 blanket, 1 washcloth, 1 towel, 1 uniform, 1 cup, 1 spoon. MCJ has awarded 180+ high-school diplomas in recent years, thanks to a GED program—with qualified teachers for it as well as ESL courses.

“Columbus Stockade Blues” was written by two brothers from Chattanooga.

This take on the tune by Doc Watson andDavid “Dawg” Grisman is

one stellar example of being busted “way down in Columbus, Georgia.

Female trauma groups are offered inside jail through Hope Harbor (physical abuse) and the Family Center (sexual assault). “Hurt People Hurt People” is a counseling mantra of these groups, Richardson says.

Floor 2 of the new tower holds programs for men: Fatherhood, Faith-Based Substance-Abuse Recovery, and Veterans, who are housed in their own dorm.

“The number-one group for incarceration increase in America right now is veterans,” Richardson says.

The compounding disaster that is the downward spiral of substance abuse is familiar territory for Richardson, a recovering addict whose former life was as a political operative in South Florida.

“We’re going through a time in our military right now where we’re deploying soldiers in combat without a rear area. In Vietnam, it was 6 weeks in the bush, 2 weeks at the beach for R&R. If you go to the Middle East, you’re constantly in harm’s way. There’s no relief. We’re seeing more instances of PTSD and its substance-abuse link. And non-identification of the issue is a problem; it’s hard to admit you have a mental-health problem. They think, ‘I just get tense sometimes and a couple of beers calms. Smoke a doobie. Whatever. But it accelerates, so …”

Asked about a “Don’t Be the Dealer” poster tacked to a door—encouraging all to properly trash their old prescriptions—the chaplain says he’s not sure smuggling of prescriptions is a big issue.

“Besides weapons, it’s street drugs they try to smuggle,” he explains. “We have to do a cavity search on everyone. Again, to protect the inmate. If they hide a bag of heroin by swallowing it, if that bag bursts in their stomach, it’ll kill them.”

Richardson says, “We’re the ones writing the scripts,” when asked about potential inmate abuse of prescribed pills paid for by the taxpayer while they claim a ‘dope sick’ medical condition.

“The worst heroin addict’s withdrawal is like a bad case of the flu,” he says. “If you have a serious pain condition, you’re going to get treatment under close supervision. Heroin withdrawal is non-medical. The worst withdrawal that exists comes from alcohol. That can kill you. If a guy comes in blistered drunk, like that one we saw earlier in the Sally Port, he might need to spend a few days under observation.”

Among the many cat-and-mouse games inmates play behind bars comes in the hunt for Buck.

“Buck is whatever you can throw together in a bag and hide in the corner until it ferments,” Richardson says. “Sometimes I think it’s the inmates’ job to see if they can get away with it. One time, this guy says to me after deputies busted a big ol’ bag of Buck, ‘Oh no! We were going to get REAL drunk tonight.”

“The Comfort to Keep Going”

Sitting in MCJ’s break room as colleagues eat lunch at nearby tables, Chaplain Neil is asked about his own mental health.

Is his job’s grind taking its toll on him?

“No—this is invigorating,” Richardson says. “Because, first of all, I’m called. God wants me to be a chaplain in a jail and so would never put me in situation where it’s going to fry me. My biggest personal prayer request is that I never get cynical. And that I’m always willing to get hurt. But I think that’s a responsibility of anybody working in mental-health counseling, spiritual-health counseling or anything like that.”

“There are going to be people who don’t finish the course that you invest in. It’s going to hurt. But then I can turn to an Almighty God to give me that comfort to keep answering His call and give me the comfort to keep going.”

“Going to Jail with Chaplain Neil” is the first installment in the upcoming series “Caught Up: Criminal Justice in the Chattahoochee Valley.” It was inspired by a visit to the jail in October 2018, when Chaplain Neil Richardson helped host an On the Table lunch to discuss criminal-justice issues. During that lunch, Richardson provided the following stats:

- 85% of inmates are incarcerated for issues related to drugs and alcohol

- 80% of inmates will be back in jail within the first six months after release

- 1 in 13 Georgians are under state supervision (parole, incarceration, etc.)

- A juvenile delinquent will cost $3 million in the legal system over their lifetime

A series of profiles told in words, audio, photography and videography, “Caught Up” seeks to further the understanding complex criminal-justice issues in our community. Electric City Life will publish this six-part series through September.

“Caught Up: Criminal Justice in the Chattahoochee Valley” is made possible by an Action Grant from the Community Foundation of the Chattahoochee Valley.

Muscogee County Jail, 2019

So, So proud of you. YOU found after all these years, YOUR PURPOSE and MISSION