Among the many cheap-shots at Columbus in his 2007 book The Big Eddy Club, Englishman David Rose’s observation “the city takes up far more room than its inhabitants” is perhaps his most astute.

Rose went on to compliment the “towering gardens” he found on Columbus’ large residential lots. It’s a charming characteristic of the city and it comes rooted in a Deep South agrarian society and held seemingly sacrosanct in its residential zoning codes. However, some developers—from out-of-state companies to self-taught historic-house renovators—have long argued that such local regulations have kept Columbus real-estate market stuck in the 20th century and unattractive to investment.

And as we learned from a City Council Work Session Tuesday morning, changing these rules on how we build our homes will be hard.

Soon after delivering his presentation on the so-called Tiny House Appendix—an update to Georgia State Residential Code that took effect Jan. 1 but requires local approval before it’s implemented—Director of Building Inspections & Code Enforcement Dept. John C. Hudgison described City Council’s response as “lukewarm” and that a series of public-input meetings is needed for tiny houses to again be considered in Columbus.

Tiny House Examples from Georgia Dept. of Community Affairs:

Hudgison’s update arrived via email sent to interested parties that included urban-renewal stewards Uptown, Inc. and Home for Good, the “alliance to end homelessness” program of the United Way of Chattahoochee Valley. Email addresses also came from participants in the Tiny House Class & Workshop that Inspections & Code hosted Oct. 10 in a hospitality suite at the Civic Center.

The five-hour session was sponsored by local car-services kingpin PTAP and Atlanta-based MicroLife Institute, located in a 180 sq. ft. office along the BeltLine and whose Executive Director Will Johnson came to the Civic Center with a 150 sq. ft. tiny house in tow.

“We’re trying to normalize small spaces,” Johnson told the crowd taking a look into the model dwelling in the parking lot at 9 a.m.

Hailed as an innovator who helped convince the City of Atlanta to adopt a tiny house-friendly ordinance in June 2017, Johnson said this normalization would encourage residents in communities such as Columbus to “allow them into their neighborhoods.” Asked about the potential to help solve homelessness/affordable-housing issues, Johnson said the tiny-house movement “is not a silver bullet, but it’s a part of the conversation.”

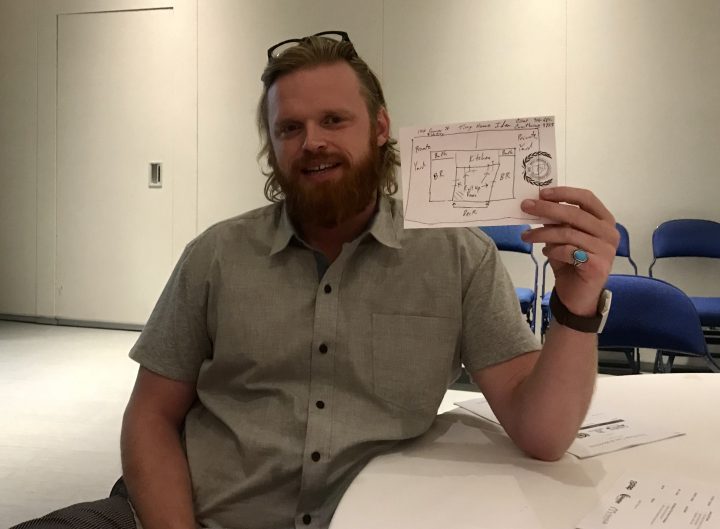

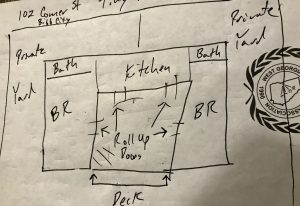

That conversation also includes the vision Clint Cawthorne has for the vacant lot at 102 Comer St. in Bibb City: a 2 bed, 2 bath tiny house of four structures around a communal outdoor space/deck and surrounded by a private yard.

The problem? It doesn’t fit the city’s 50 ft. frontage requirement for single-family residential development.

Cawthorne says he’s restored several historic homes, first an abandoned one in Lakebottom and now three in Bibb City, working with his “best friend and business partner” Thomas Rogers (RevitaHome).

“I enjoy renovating old historic homes,” explains Cawthorne, who once recruited co-worker buddies at 11th and Bay to lay out 12 pallets of reclaimed granite he scored from Flat Rock Sand & Gravel. “But I wanted to do more.”

So he bought the Comer Street property—“looking terrible, burned down to a hole on the lot”—wanting to build, choosing against an easy choice of land banking (donothing and wait for area appreciation to sell).

“I’d rather do something good for the community and surrounding neighborhood,” Cawthorne says, “and do something aesthetically pleasing.”

He says existing regulations against modular and free-build homes limit what he can do on the small lot. However, local adoption of the Tiny House Appendix would provide “a lot more options.”

Hudgison said during his Q&A with participants at Tiny House Workshop his role was “to gather feedback” for his City Council presentation.

He reported that the “lukewarm” response included Councilor Mimi Woodson’s concern for impact on the fabric of historic neighborhoods. Councilor Glenn Davis expressed worries of AirBnB taking over tiny-house properties in town and suggested regulating them like RV Parks.

So in a city/county with roughly 70,000 residential parcels, Hudgison and others now consider how to raise public awareness and support for allowing among them tiny houses. That definition applies to single-family structures less than 400 sq. ft. and includes—maybe more shocking to the status quo—homes crafted out of shipping containers. Often completed with astounding architectural design, this cost-effective, simple-life trend is now with codified support (as of July 17) in the 42-year-old Georgia Industrialized Buildings Program.

“It’s about how to make city residential housing regulations more inclusive and how to make them more attractive for redevelopment,” Hudgison says of an effort that one day may invite tiny houses to town.