“The kids decided they weren’t going to put up with it anymore.”

“How happy I was to come here and not have a seat!” Ibrahim Mumin exclaimed to an overflow audience at Mildred Terry Library in the Liberty District last night.

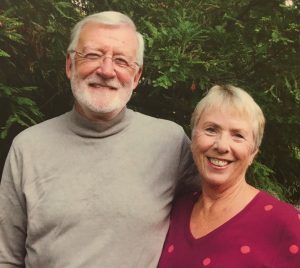

Special guest for the free community event featuring Wayne Wiegard, author of the just-published Desegregation of Public Libraries in the Jim Crow South, Mumin was back in his hometown for this appearance and one tonight at the Columbus Museum. The events combine to celebrate the role he and 40 other African-American teens had in desegregating local public libraries by organizing “read-in” protests conducted in silence in the summer of 1963.

“I’m 71 years old and I’m so glad I’m not here just talking to other 71 year olds,” Mumin, who grew up to become an educator in Washington. D.C., tells the crowd. “There are black kids here. There are white kids here.”

Adopting the Islamic faith in 1978, Mumin still went by his given name Charles Porter at age 15 when Columbus police detained him for a few hours following a read-in at then-Fourth Avenue Library. For the first time, Mumin will join fellow teen activists (Christine Dawson, Gwendolyn Jackson, and Cleopha Tyson) to share their stories in “The Struggle to Desegregate Columbus Public Libraries” panel discussion at the Museum, free and open to the public, starting at 6 p.m.

“We have to share this lost history,” Mumin says of the efforts to desegregate public libraries to the crowd at Mildred Terry. He seeks out Sylvia Bunn, the branch manager and “real-deal connection to Mildred Terry,” the beloved late librarian who led the city’s first “colored” library when it opened five years after local African Americans first approached city leaders in 1947 to ask: “When will a public library be available to us?”

Next, Mumin connects his Christian upbringing to Muslim teachings while thanking Wiergard for his work documenting “what could have been a lost history.”

“The ink of a scholar is more precious than the blood a martyr.” he says in praise of Wiegard, an American Studies professor at Florida State University who co-wrote Desegregation of Public LIbraries in the Jim Crow South with his wife, lawyer/professor Shirley.

“Columbus, Georgia has produced some of the brightest people in the world,” Mumin tells the packed room with the art of Alma Thomas on its walls. Praise continues for Branch Manager Sylvia Bunn. “the real-deal connection to Mildred Terry,” he says in reference to the beloved late librarian, a community fixture for decades while leading the library. At the time located in the heart of African-American culture Columbus, Fourth Avenue Library was built between Fifth Avenue School, Booker T. Washington housing project, and black-owned businesses in Liberty.

Wiegard concluded his remarks on the American Library Association conference last summer in New Orleans, where the group formally apologized for its silence over segregation at this sacred national institute. During the concluding Q&A, he was asked if the NAACP organize the silent read-ins starting up all over the South.

Reading from Ledger-Enquirer commentary at the time, Wiegard repeats accounts of fist fights between black and white boys at public spots such as pools and parks. Parents should instruct boys of both races “to carry themselves in a dignified manner and not react to tense situations,” an editorial stated in summer 1963 in its call for calm in a city simmering with racial rage in days before Jim Crow boiled over.

Serving as the moderator of the Museum panel discussion, Wiegard’s compelling presentation at Mildred Terry featured research collected for his book. Such archival info came not from white newspapers such as the Ledger but black publications such as the Atlanta World. Digging deep, Wiegard followed the case of a 17 year old black boy arrested for fighting a 30 year old white man at a public library, who approached then teen and close-fist shoved him. Both were booked for disorderly conduct. The white man was acquitted. The black teen was fined $17.

Wiegard concluded his remarks on the American Library Association conference last summer in New Orleans, where the group formally apologized for its silence over segregation at this sacred national institute. During the concluding Q&A, he was asked if the NAACP organized the silent read-ins starting up all over the South.

“It wasn’t the NAACP or any such Civil Rights group, Wiegard answers. “It was the kids deciding they weren’t going to take it anymore.”