Columbus historical attractions

& America’s cultural reckoning

There used to be a joke told around here that went something like this:

“Westville: Where It’s Always 1850. And Columbus—where it’s still 1950.

Today, that joke no longer applies.

For one, Historic Westville, an antebellum living-history attraction in Stewart County for 90 years, has moved to Columbus and since dropped that long-serving slogan. It will open spring 2019 with an expanded

educational scope to include influences from the longleaf pine to pre-Colonial Native American life.

And as for Columbus being stuck in the past, the city marches further into the 21st century no longer clinging to its Confederate past. Engineered by a progressive mindset two generations post-Civil Rights, the city now presents itself as open to all. A place for businesses to build and for artists to create. Home to the last battle of the Civil War, Columbus (whether due to official decree or new attitudes) is no longer tolerant of public displays that celebrate the city’s role in America’s defining conflict.

The local trend mirrors a seachange in how our history is told sweeping the South since Lost Cause-inspired 2015 Charleston, South Carolina church massacre riots around the removal of a Robert E. Lee statue in Charlottesville, Virginia in August 2017.

Nowhere is this shift more obvious than at Linwood Cemetery, home to the South’s first Confederate Memorial Day.

Nowhere is this shift more obvious than at Linwood Cemetery, home to the South’s first Confederate Memorial Day.

The week after Charlottesville, the two Confederate flags that flew at Linwood disappeared. They were said to be stolen.

Not true.

Turns out, the man who said they were taken likely as an act of vandalism is the same man who took them down in the dark of night.

He was also the man in charge of their upkeep as the leader of the local Sons of Confederate Veterans, who were given permission to erect flagpoles and raise flags over two Confederate memorial sites inside Linwood by a 1994 City Council resolution.

“The roles of everybody”

“If you want to know the history of Columbus, you come to Linwood,” says. Jane Brady, executive director of the Historic Linwood Foundation.

“You come if you want to know about the founders—the people who built Columbus,” Brady continues, speaking inside the nonprofit’s office just inside the cemetery gates.”Linwood is older than the city itself. Truman Hope Thomas, son of the first surveyor, was buried here when his father brought him to the highest point north of the city. That was in March 1828. Columbus didn’t come into being until July 1828.”

The oldest operating institution of city government, Linwood was called City Cemetery until the mid-1890s.”The city works hard at keeping the grounds straight,” Brady says. “We work hard at doing the preservation. We work hand in hand with the city.”

The oldest operating institution of city government, Linwood was called City Cemetery until the mid-1890s.”The city works hard at keeping the grounds straight,” Brady says. “We work hard at doing the preservation. We work hand in hand with the city.”

HLF’s 22nd annual Fall Ramble on Oct. 18 featured for the first time a slave among its cast of storytellers. Dave Gillam played the part of Josephus Hawkins, buried alongside the family that owned him, one of three African-Americans in the cemetery. Josephus was included because he fit this year’s theme exploring Linwood’s Old Section, Brady explains, and not because of any deliberate attempt to showcase a slave.

“We’ve always taught the roles of everybody in all of Columbus history,” she says.

As for the why two Confederate flags fly at Linwood?

“We had nothing to do with that,” answers Brady. “That’s between the city and the Sons of Confederate Veterans.”

“You can’t accomplish anything by being a bunch of hot-head rednecks.”

“No, they weren’t stolen,” says Charles Hartley, Jr., commander of Benning Camp, Sons of Confederate Veterans. “The previous camp commander, Brandon Dorrill, first said they were stolen but then admitted to taking them down right after Charlottesville. He told us that we needed to take them down until this cools over.”

Mayor Teresa Tomlinson didn’t order them taken down, Hartley says of one conspiracy theory, but she did request a meeting with the Sons of Confederate Veterans after they went missing.

“With the national discussion about our nation’s Civil War history, our state’s monuments and our current community, I informed the SCV that we would no longer allow Confederate flags on those poles,” Mayor Tomlinson writes in an email to Electric City Life. “First, because it was divisive, and second, because it was not historically accurate. While the Confederate flag was a battle flag it was not the flag of the State of Georgia at the time or the flag of the Georgia civil war regiments. After a meeting and discussion with the SCV, we agreed that they could fly either the historically accurate flag of the State of Georgia at the time of the deaths of the soldiers, or they could fly the current state or U.S. flag. We appreciate their cooperation in assisting us in honoring the sensibilities of our current citizens, while appropriately recognizing the war dead.”

Not present at the meeting, Hartley says the local SCV was represented by its state commander as Dorrill had stepped down amid “quite a bit of turmoil in the camp.” (Repeated emails and voicemails left for Dorrill seeking comment were not returned.) “State told us to just leave it alone,” Hartley recalls of a decision that led to the group accepting the offer to fly the current Georgia state flag.

An homage to the lesser-known Confederate national flag, Georgia’s flag since 2003 was born in out of a political compromise after years of debate about replacing the 1956 version, which added the widely recognized battle flag in defiance of the looming Civil Rights Movement. The push to remove the rebel flag from Georgia’s flag started in the mid’90s, around when Columbus City Council passed resolution 444.94.

Approving by 6-4 vote along racial lines on Oct. 4, 1994, it called for the Camp Benning SCV to pay for and maintain two 35-ft. flag poles and two 6×10’ Confederate battle flags to be flown 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, with others “possibly being flown on Confederate holidays.”

The proposal had been shot down 7-2 by City Council a few months earlier at its March 28 meeting.

The reason?

“Bad timing,” a councilman said at the time, as it coincided with the controversy over Nation of Islam leader Louis Farrakhan coming to town, plus a hot-button school desegregation issue.

Linwood, with a major battle here and a huge hospital nearby, holds about 100 graves of known and unknown Confederates. This heritage explains why Confederate Memorial Day originated at then-City Cemetery. The flags approved by City Council were dedicated on April 26,1995—Confederate Memorial Day.

Hartley says the local SCV cited resolution 444.94 in talks with the city but were unable to prove claims to the sites. The agreement to fly the current Georgia flag wasn’t a compromise, he adds, but one forced upon them.

“There’s been too much emotion over this the last 4-5 years, as we’ve seen,” the Harris County resident concludes on a cold November morning at Linwood in regard to the bigger national debate as well as the local decision for non-confrontational compliance. “You can’t accomplish anything by being a bunch of hot-head rednecks. I don’t want that to be our legacy and I’m of the thinking that things can always get worked out.”

However, Hartley is then quick to point out the hypocrisy he finds with a Confederate flag flying outside the National Civil War Naval Museum at Port Columbus.

“It can be a difficult story to tell.”

A quick visit to check this claim shows only an American flag flying high above the museum located on space grounds between Victory Drive and the river.

But removal of a first-pattern Confederate national flag from that same towering flagpole came just a few months ago in September.

“The flag was taken down due to its poor condition,” Jonathan Perkins, director of communications and marketing at the National Naval Civil War Museum, explains in a email. He adds that a 34-star United States flag was also taken down and these historic flags “are expensive to replace and to keep flying.”

The museum moved into its current 40,000 square foot location in 2001 following a change from its original name: Confederate Naval Museum, created in 1962 to house its showcase the dredged-up CSS Jackson, an ironclad battleship built at the Iron Works before catching fire and sinking into the Chattahoochee River a short distance south. The removal of Confederate from the name came as a result of political pushback in the late ‘90s, led by then-Councilman Nathan Suber, against the use of city money in paying for the move to a new $8 million facility.

The museum moved into its current 40,000 square foot location in 2001 following a change from its original name: Confederate Naval Museum, created in 1962 to house its showcase the dredged-up CSS Jackson, an ironclad battleship built at the Iron Works before catching fire and sinking into the Chattahoochee River a short distance south. The removal of Confederate from the name came as a result of political pushback in the late ‘90s, led by then-Councilman Nathan Suber, against the use of city money in paying for the move to a new $8 million facility.

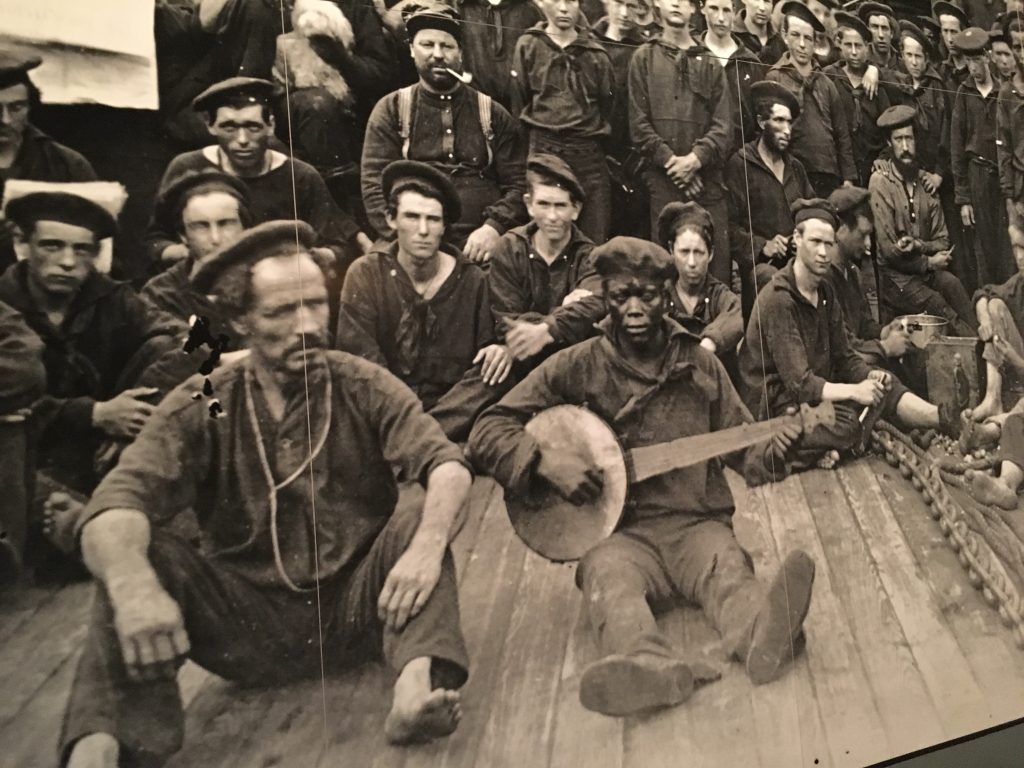

During his five years thus far, Perkins says he’s seen the museum’s educational approach evolve,“telling stories you won’t hear anywhere else to diverse audiences from all over the world.” It offers everything from seminars with leading scholars to hands-on summer camps to afternoon tea socials.

Meeting on a Monday afternoon in the lobby with colleagues Jeff Seymour, director of history and collections, and Brandon Gilland, director of education, Perkins names several African-Americans that’ve been featured in museum programming: Robert Smalls, Moses Dallas, and famed architect and bridge-builder Horace King, a slave-owning former slave who did some design work for building the Jackson and had four sons that worked at the Iron Works.

“It came be a very difficult story to tell,” Seymour says of teaching Civil War history. “And not one typical of what most people think as to, ‘This is slavery. This is not.’

“It’s always been a combination of the Columbus story and the national story,” Seymour adds about the museum’ approach. ”And the connection to the river, which is why Columbus turns into the second most-important industrial site in the South. Now it’s only thought about as a travel impediment or just recreational.”

“It isn’t one flag. It isn’t four years old.”

“It won’t be where it’s always 1850 anymore,” Director of Interpretation Stephan Zacharias says of Historic Westville once it opens in Columbus. “It will be full 19th century out here at Westville.”

Guides in period dress will trace Native Americans back to when the trade winds first brought them to North America. There will be an area devoted to the longleaf pine.

“It’s impossible to do the 19th century here and not deal with the longleaf pine ecosystem,” says Zacharias, a theater major who has become a living-history pro with 15 years experience, coming to Columbus after stints at Historic Williamsburg in Virginia and Georgia Museum of Agriculture & Historic Village in Tifton. “One thing people don’t understand is their ancestors’ connection to the land. It was part of your daily life. It was how you feed your family, how you make your money. Everything you do is associated with that ecosystem. We’re getting back to that way finally but the connection has been lost.”

With astounding command of regional history for a transplant from Oregon, Zacharias is the son of acclaimed writer Karen Spears Zacharias, an Army brat who graduated from Columbus High and wrote for Ledger-Enquirer.

The moved to Columbus “was a no-brainer,” he says, hoping for overflow from the National Infantry Museum just across South Lumpkin Road along with placing the attraction along the river. Stewart County officials imposed red-tape and fees on a move they opposed, one of the reasons the grand opening was delayed from an original Oct. 20 to now hopes for early spring. Another delay comes from the required conversion of these delicate antebellum structures to meet ADA compliance, adding items from wheelchair ramps to exit lights.

“Interpretations are going to be completely different,” says Zacharias. “The focus before was on stuff. Now we’re going to be talking about who was using that stuff. Now is an opportunity to show a lot of different cultural groups. There are many Souths. It isn’t one flag. It isn’t four years old.”

The village area features structures from around Georgia including the Climax Presbyterian Church built 1840 and the McDonald plantation home.

The village area features structures from around Georgia including the Climax Presbyterian Church built 1840 and the McDonald plantation home.

“There you’ll see how 10-22 slaves were housed at the back of a house where they served a family of 5 to 6 living inside,” explains Zacharias. “You see how everyone was living together. All bumping shoulders in tight quarters. Nobody’s saying it, but everybody’s a little afraid. The slaves are scared they’re going to screw up and they’ll get killed for it. The guys in the main house are afraid there’ll be an uprising and they’re going to get killed.”

“We’re not here to provide you answers,” Zacharias says in how the tough history lessons will be taught. “We want you to walk away inspired enough to do your own research. Do a Google search, read a book, and come back a few days later and challenge us on our interpretations.”

Since one of the topics is about flags, I don’t have the connections that you have as to who to talk to regarding the tattered flags that are embarrassingly shredded and limping at the Chattahoochee Promenade.

If they can’t be adequately replaced, they need to be taken down immediately.

There are a few inaccuracies here.

1. Westville was founded in 1966, making Westville fifty years old as the board trustees began moving it. The ninety-year mark they cite is a stretch. I suspect that this new board wants to avoid accusations that Westville was a cultural treasure of Stewart County. So, they mark Westville’s founding to the handful of buildings that were moved to Westville from Jonesboro, Georgia, a place that was founded in 1928. The fact is, the Stewart County version of Westville was eligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places when the board decided to move it to Columbus. The move caused an automatic ineligibility for the Register. So, it is undeniable that Westville was a Stewart County treasure.

2. I see in the photos of the Westville buildings things that don’t belong from a historical standpoint. One is the Celtic cross in the pediment of Climax Church. That was never there, and it would not have been in any rural building anywhere in Georgia in the nineteenth century. In fact, it looks quite modern.

3. “The move to Columbus was a no-brainer.” I dispute that assertion with every fiber in my soul and body. Stephan Zacharias, who made the statement, is a forthright person, but he does NOT know what happened twelve years ago, long before he was hired. In those days, the leadership forced failure on the village, beginning with an unnecessary protracted argument with the Lumpkin City Council around 2007. That director was hired with the specific instruction to maintain and improve visitation. When he failed to do so, rather than face certain dismissal, he began to sabotage the village. He forced visitation down, instead of improving it. He ended the local volunteer program. He ended the crafts program. He insulted the merchants on the square in Lumpkin. He talked the executive committee into new by-laws which dumped local Trustees and stacked the board with young Columbus trustees. The move was decided on with one of those preposterous SWOT analysis retreats. It supposedly “proved” that Westville needed to move, but in fact, it just confirmed that a stacked Columbus board would vote to move. I invite you to interview local Stewart Countians about that director who engineered all that if you doubt my veracity.

At this point, I don’t wish ill for the current staff. But, let’s don’t do revisionist history. Columbusites should know that Westville was legally stolen from Stewart County.

Mac –

Thank you for taking the time to read this story and add your comments in response, an important perspective as a long-time Executive Director of Historic Westville and community leader in Stewart County.

You are correct in that my reporting (based on source-provided info) dated Westville back 90 years to its origins in Jonesboro. I should have made a clear distinction between that and the organization that ran the attraction since 1966.

I have also invited Westville Director of Interpretation Stephan Zacharias to add any additional comments/insight he may want to provide in response to the article and/or your response.

Sorry about the long delay in responding (a WordPress upgrade hid my typical comments alert) but I appreciate you adding your thoughts.

Thanks, Mac.

FE

Thank you to Electric City Life and to Mr. Frank Etheridge for including Historic Westville’s efforts in regards to the local area antebellum attractions. Additionally, I would like to thank Mr. Moye for his comments and his efforts in maintaining and furthering the legacy of Lt. Col. John Word West’s initial vision and efforts at his Fair of 1850 that had been located at Jonesboro.

As a professional Living History & Cultural specialist, I accepted a role here at Historic Westivlle in the hopes of making sure that I do what I can to preserve and advance the vision and mission of all those who have previously put forth the effort to advance Lt. Col. West’s legacy.

While Mr. Moye and I will probably always disagree on whether or not Historic Westville could have financially succeeded in Lumpkin, I firmly believe that on all matters else regarding Historic Westville, especially in regards to preservation and historic interpretation we in all probability could not agree more.

There are and continue to be many factors that are way outside my control, however, I am available to any and all who wish to discuss these matters in further detail. Hopefully, for a long time to come Historic Westville can be a place where all people can come together to openly and honestly discuss the difficult and complex history of the Wiregrass Region in the 19th Century and beyond.

Please feel free to stay up-to-date with Historic Westville’s progress by following us on Facebook. To find out more information on Historic Westville please e-mail: office@westville.org or to make inquiries related to the historic interpretation at Historic Westville you can contact me by emailing: interpretation@westville.org

Thanks for commenting, Stephan.

As of Thursday, February 7, 2019 my affiliation with Historic Westville has been terminated. While I stand by my comments in this article and in my previous post here on this page. I do not endorse or support anything produced by Historic Westville beyond February 7, 2019. Thank you all for the opportunity I was given.

Stephan –

Would you please call/text me when you get a moment? 706.593.1916

Frank