When Najee Dorsey talks about Black Art in America, he talks not in the singular but in terms of “Us,” “We” and “Our.”

“Our greatest strength is our flexibility, our agility,” the 45-year-old Arkansas native says of his critically, culturally and commercially booming business. “If we were a corporation, it would take too much time to cut through all the bureaucracy. If we’re more agile, we’re more versatile.”

Dorsey established Black Art in America (BAIA) eight years ago in Atlanta. Four years ago, the CEO chose to call Columbus home. He spent some time here for work on his first major solo exhibition, Leaving Mississippi: Reflections on Heroes and Folkmore.

“Mixed-media collage landed me my show at the Columbus Museum,” he recalls, noting one favorite, an homage to bedeviled blues forefather Robert Johnson. “We came down here several times in preparation for the show, saw good things happening here and we decided to make it our home.”

“I say ‘we’ and ‘our’ when I speak of BAIA in general,” Dorsey explains, talking Tuesday morning in the sunlit Swift Mill Loft that now serves as office headquarters and will celebrate its grand opening as a fine arts gallery this weekend with an inaugural open house.

“I think it’s a better mind-frame to work from,” he continues of his persistent plurals. “Plus, my wife Seteria helps run the company. No way I could do it alone. But I want to set a vision for what we’re doing.” With a concerted effort “to be very visible as the head of the company” (which has no employees, using contracts for terms and deals with clients, collectors, and consultants), Dorsey says BAIA’s mission is to “document, preserve, and promote the contributions of the African-American arts community.”

With a concerted effort “to be very visible as the head of the company” (which has no employees, using contracts for terms and deals with clients, collectors, and consultants), Dorsey says BAIA’s mission is to “document, preserve, and promote the contributions of the African-American arts community.”

“Compared to cities of similar size, there’s a pretty strong argument for Columbus having significant artists in general,” the gracious gentle giant says of his adopted hometown “And not just Alma Thomas. There’s ‘Blind’ Tom [Wiggins]. Bo Bartlett. Amy Sherald. Myself.”

The sleek, yet gritty blue-collar vibe, of BAIA’s converted industrial space at Swift Mill has a balcony facing east towards the railyard. The neglect-battered Claflin School—established in 1868 as the city’s first school open for black children—rests about 100 yards to the west along Fifth Avenue and will soon be restored into 44 apartments. Just up the small hill to the north is a section of Linwood Cemetery dedicated to the many Confederate soldiers that died in Columbus hospitals.

“It’s a step up in in the look and feel of our setting. Aesthetically, it has the look of a national headquarters,” Dorsey says of BAIA’s new digs, formerly housed in a 17th Street bungalow. “We’re growing the company and it’s designed to show a level of success—because we have important work here. The space is to showcase the artists we work with.”

Artists displayed in the loft include “iconic” late printmaker/sculptor Elizabeth Catlett, “rising star” Alfred Conteh, and “the foremost African-American sculptor today,” Woodrow Nash.

Dorsey confesses he dropped out of his partial-scholarship at the Memphis College of Art after two classes. “The structure of school wasn’t for me,” he explains. “If something doesn’t interest me, I’m not going to give it my attention.”

Starting out with a focus on blog posts and sharing content on social media, “our business model has changed and keeps changing. We learned we had to do sales to generate revenue. And then we leveraged our status as a media company to carve out our niche and to create events.”

After creating an online sensation with its media coverage of Art Basel, arguably the world’s eminent arts gathering every winter in Miami, with the viral hashtag/catchphrase “Do YOU Basel?” in 2012, the following year event leaders asked BAIA to curate its own programs for it. Dorsey two weeks ago returned from Philadelphia, where 5,000 people attended a BAIA show at the Historic Belmont Mansion and Underground Railroad Museum.

“We’ve been all over the country but never Philly and it was really tugging at me,” Dorsey says. “My business model is instinctual; I take the temperature and go where the winds of the ancestors are pulling me.”

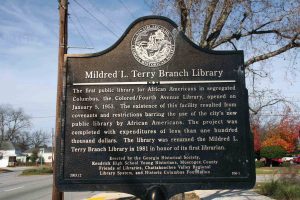

“He’s a big enough name that he can pick and chose any project,” Chattahoochee Valley Libraries Director Alan Harkness says of Dorsey. “We’re just thrilled he picked to do ours.”

In celebration of the Mildred Terry Branch’s anniversaries next year (10th in the new building, 66 years since first opening its doors as the first public library accessible by black residents), “We wanted to capture its story in a mural,” Harkness explains of an in-progress work measuring 8 ft. x 40 ft. “The history of that library is really the history of the Liberty District.”

The commission was paid for by the Muscogee County Library Foundation and marks the second public-art mural in the Liberty District. To help inspire and inform Dorsey, a public- engagement event was held last week at the library.

“A lot of older people showed up on a stormy night,” he says, “but it was a really great night. I feel privileged to hear their stories of growing up in the area and the service and dedication of the people that worked there.”

“A lot of people had strong and fond memories from the library,” Dorsey says, seated in in his studio area at BAIA’s Swift Mill Loft and showing a sneak-peek look at his mural, his design fresh back from the printers to “review with the powers that be.”

Moving left to right, the horizontal work depicts Civil Rights-era protests to open the library, “a Mt. Rushmore” of its three leaders from first Terry to Sylvia Bunn today, the book mobile that brought books to kids in the Liberty as well as Harris County (where Jim Crow banned black citizens from all libraries), “original urban gardeners” in the Booker T. Washington housing projects, and neighborhood product (and acclaimed fiction author) Shay Youngblood.

Moving left to right, the horizontal work depicts Civil Rights-era protests to open the library, “a Mt. Rushmore” of its three leaders from first Terry to Sylvia Bunn today, the book mobile that brought books to kids in the Liberty as well as Harris County (where Jim Crow banned black citizens from all libraries), “original urban gardeners” in the Booker T. Washington housing projects, and neighborhood product (and acclaimed fiction author) Shay Youngblood.

Rendered as vibrant and innocent, a young boy and girl whom Dorsey met at the meeting are found to the far right.

“It was a struggle to get that library open and Shay represents what comes out of this community,” Dorsey explains. “At the public-engagement, it became clear that the narrative to me is the history of this library, the workers here. It was heartwarming to see all the love Miss Sylvia Bunn and her staff give everyone that walks in that door. To me, they’re saints. The unsung heroes who roll up their sleeves and get to work for little to no recognition. l But the impact they have—it’s hard not to come people like that in a community that calls itself progressive and moving forward.”

Free and open to everyone, Black Art in America’s Fine Art Gallery Grand Opening takes place 3-8 p.m. Fri., 10-8 Sat., noon-6 p.m. Sun. Click for Info or to RSVP.

[…] Anderson in the Liberty Theatre lobby in front of a painting by Columbus-based artist Najee Dorsey. […]